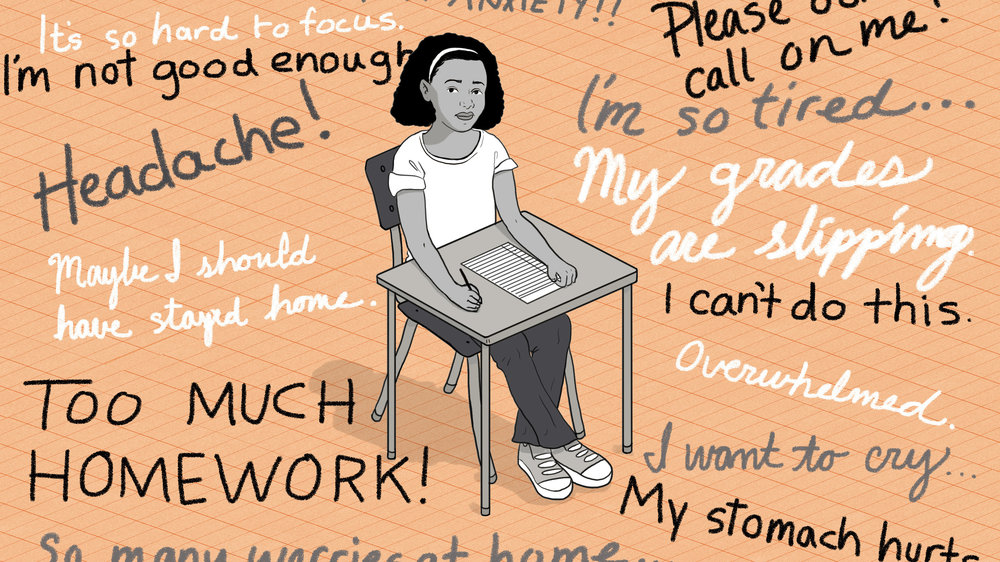

Mental health issues have reached epidemic proportions in contemporary western societies, and our educational institutions are not immune (Aggarwal et al., 2015, p. 491). During my professional experience, multiple teachers from three different high-schools have expressed how common anxiety, depression, body-image and self-esteem issues are in today’s high-schools. Similarly, several informed me about the full workload of school counsellors who are struggling to find time to attend to students’ various mental health needs.

When I polled teachers during my first professional experience placement with the question “who would be comfortable setting texts that focus on mental health issues?”, I received mixed results. Younger teachers were keen and willing to introduce such texts, cognisant of the broader problem of mental health and believing that the classroom is a safe and proper place to discuss serious matters. On the other hand, older teachers were more reluctant, voicing concerns about introducing such texts lest they trigger and potentially worsen underlying mental health issues amongst students. These older teachers agreed that there was a problem, but felt it was too risky for them to become involved with, especially within today’s context of heightened teacher scrutiny from parents and the media. All teachers present expressed an interest in learning from a successful model of implementing such a program, because they weren’t sure how best to address this problem.

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of academic literature regarding the role that high-school English teachers could play in remedying this social issue. Bibliotherapy and expressive writing are proven by various academic studies to improve individuals’ mental health; yet the usefulness of such techniques for improving the mental health of a whole class has been untested (McCullis & Chamberlain, 2013, p. 34; Lepore & Smyth, 2002, pp. 12-23). On a macro level, whole school mental health awareness policy initiatives have successfully improved adolescents’ mental health literacy; but this has not led to a deliberate focus on engaging with set-texts which raise mental health concerns (Wei et al., 2013, pp. 112-116).

Akin with how US educators have tackled race tensions that spill over into classrooms, I believe that teachers need to lead “difficult conversations” surrounding mental health issues to sufficiently prepare our 21st century students for the challenges of adulthood (Copenhaver-Johnson, 2006, pp. 13-16; Sherman, 2017, pp. 292-294). English classrooms, with their focus on critical thinking and personal engagement are poised to lead such conversations (Wolk, 2009, p. 667). From my perspective, the point of contestation should not be whether we introduce these texts or not; but instead, how do we incorporate texts that focus on mental health issues safely into class discussions?

There are several steps that need to be taken to reach this goal. Firstly, a safe classroom setting must be supported by a school-wide mental health program such as MindMatters, which provides mental health training for teachers and introduces procedures to support students affected by classroom content (Wyn et al., 2000, pp. 594-598).

Secondly, teachers need to have a comprehensive understanding of their students’ medical history. If students have experienced abuse or past trauma, then some texts should be avoided altogether.

Thirdly, teachers need to gauge their students’ personalities and maturity levels. Discussing texts that deal with serious mental health issues can be problematic if the class is unable to engage with the text’s themes maturely and compassionately (Knickerbocker & Rycik, 2002, p. 199). Instead, it would be preferable to wait for students to mature before introducing such texts, as inappropriate comments can invalidate the experiences of affected members of the class.

Lastly, parents and carers must be actively engaged partners throughout the process.

In a way, students have been exploring texts that focus on mental health issues for centuries, the only difference being whether teachers highlight and classify these issues or not. For example, Hamlet’s melancholy and existential angst could easily be interpreted as depression, and his procrastination and theological uncertainty interpreted as anxiety.

Of course, mental health issues are complex and cannot always be extrapolated from classic texts. New, modern texts that deal with issues that have only recently garnered medical and public attention (e.g. ADHD, ASD, ODD etc.) must be introduced to keep pace with the next generation’s needs. Examples of modern young adult fiction texts that explore mental health issues include The Man Who Loved His Children by Christina Stead (suicide), Parvana by Deborah Ellis (PTSD; depression), Finding Audrey by Sophie Kinsella (social anxiety), and Made You Up by Francesca Zappia (Schizophrenia).

As an example, over several lessons I observed how a boy with high-functioning ASD engaged with The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night–Time by Mark Haddon in Year 12 standard English. I noted how the boy readily asked questions about the text and told me how he especially enjoyed reading the thoughts of the text’s protagonist, whom he connected with. And yet, my supervising teacher told me that he broke down during a subsequent Design and Technology class: according to my supervising teacher, the boy had become more aware of his differences from reading the text and as a result felt even more isolated from his peers. Whether this boy or the school was ready or not, he had experienced a watershed era in his life through engaging with the protagonist of his English class’ set-text. How his teacher, classmate and the school reacted to his breakdown would determine whether this was a time of growth or increasing confusion and estrangement.

During the formative years of high-school, students like this boy learn about themselves through identifying with others, both in real life and through literature. Accordingly, it is imperative that adequately trained and supported teachers lead difficult conversations within the English classroom (Hsieh, 2017, p. 295). Within our contemporary era of increasing emotional turmoil and learning difficulties amongst Australian youth, English teachers should select texts that normalize mental health issues and increase mental health literacy. Because I would prefer that students, like the boy discussed above, confront serious mental health issues amidst the safe confines of a high-school’s pastoral care model, as opposed to by themselves after high-school ends.

Hyperlinks to relevant media articles

We shouldn’t teach children about mental health

Five things schools can do to help students’ mental health

Too many ‘depressing messages’ in VCE books drives push for trigger warnings

References

Aggarwal, V., Patel, R., Zhou, C., & Hawton, K. (2015). Education and global mental health. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 2(6), 489-497.

Copenhaver-Johnson, J. (2006). Talking to Children about Race: The Importance of Inviting Difficult Conversations. Childhood Education, 83(1), 12-22.

Hsieh, B. (2017). Making room for discomfort Exploring critical literacy and practice in a teacher education classroom. English Teaching-Practice And Critique, 16(3), 290-302.

Knickerbocker, J., & Rycik, J. (2002). Growing into literature: Adolescents’ literary interpretation and appreciation. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 46(3), 196-208

Lepore, S., & Smyth, Joshua M. (2002). The writing cure : How expressive writing promotes health and emotional well-being / edited by Stephen J. Lepore, Joshua M. Smyth. (1st ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

McCulliss, D., & Chamberlain, D. (2013). Bibliotherapy for youth and adolescents—School-based application and research. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 26(1), 13-40.

Sherman, A. (2017). Difficult Conversations: As Important to Teach as Math or Science. Childhood Education, 93(4), 292-294.

Wei, Y., Hayden, J., Kutcher, S., Zygmunt, A., & McGrath, P. (2013). The effectiveness of school mental health literacy programs to address knowledge, attitudes and help seeking among youth. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 7(2), 109-121

Wolk, S. (2009). Reading for a Better World: Teaching for Social Responsibility With Young Adult Literature. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52(8), 664-673.

Wyn, J., Cahill, H., Holdsworth, R., Rowling, L., & Carson, S. (2000). MindMatters, a Whole-School Approach Promoting Mental Health and Wellbeing. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 34(4), 594-601.